Real-world Challenges in AI for Science

Next Steps in Protein Structure Prediction

Represented by AlphaFold2 [1], a variety of AI-based protein structure prediction models [13,14] successfully solve the protein structure prediction problem, but it is only the first step towards understanding protein structures and functions. There are still many remaining challenges to be solved:

Protein Multimers Current predictive models of protein structure can only provide reliable results for monomers (single peptide chain). But in reality, peptide chains can interact with each other and form complexes (multimers). In many scenarios, only by doing so can the proteins perform their biological functions correctly. In structural biology, such behavior is defined as quarternary protein structure.

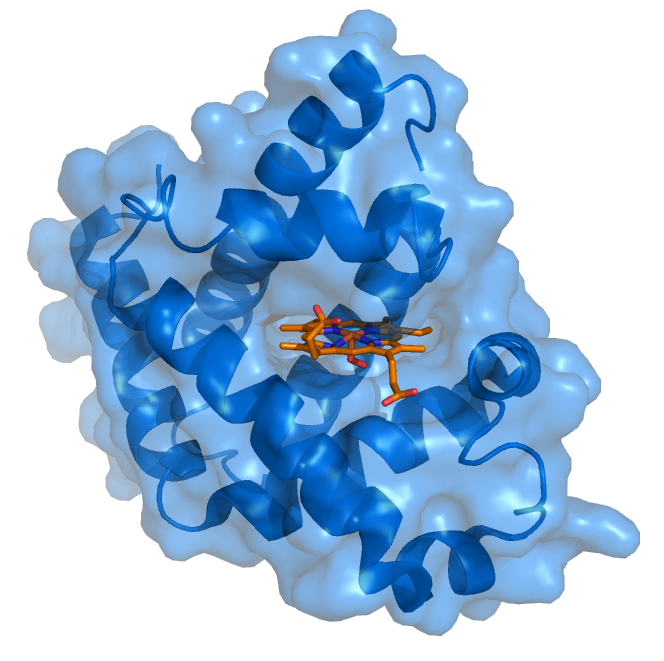

Protein-ligand Complex Protein-ligand interactions and the induced-fit models are key to understanding drugs’ potency. Small organic molecules often interact with a certain area (referred to as a pocket) in target proteins and may cause the protein structure to change significantly. Traditional computational methods, such as molecular docking, model the protein-ligand binding free energies with physical-based scoring functions, which are parametrized in an empirical and error-prune way. AI models will be a breakthrough in this area if accurate prediction of the ligand binding pose, and/or the protein structural changes during the ligand binding process can be made.

Protein Conformation Ensembles Most of the recent successful models are based on multiple sequence alignment (MSA), which can be viewed as an augmented version of “homologous modeling”. The scientific logic behind this is that proteins follow rules of evolution, so more or less, any protein found naturally is subject to have some structural similarities with those proteins in other organisms which some have been studied before. However, there are still a variety of proteins that are de novo-designed (manually designed) or lacking MSA, current models fail to provide reliable prediction results. Thus one promising direction of AI-based protein structure prediction may be the development of MSA-free models.

Quantum Mechanics

One of the central goals in quantum mechanics is to find accurate solutions (wave functions and energies) to Schrödinger equations on real systems, which is hindered by many-body problems because the dimensionality of the equation is \(3N\), where \(N\) is the number of electrons (and a real system can easily have hundreds of electrons, where the many-body Schrödinger equations can not be solved exactly. To compromise, researchers have come up with many approximation methods, such as DFT (density functional theory), to make the computational cost acceptable by sacrificing some accuracy. This work have reached great achievements in many areas such as material science, but in cases where the DFT results are not accurate enough, researchers have to rely on more accurate but more time-consuming methods (CCSD(T), with a computation complexity of \(O\left(N^7\right)\)). Recent work, such as DeePKS [15] and DM21 [16] have been proposed to tackle this issue with AI models, but are still far from perfect. One particular challenge is how to represent an anti-symmetric function under permutation in a neural-network manner (wave functions of electrons are of this property).

Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computer simulation method for analyzing the physical movements of atoms and molecules. The atoms and molecules are allowed to interact for a fixed period of time, providing a view of the dynamic “evolution” of the system. The trajectory can be considered as a sample under the Boltzmann distribution of a given system and temperature. Thus, many thermodynamic properties such as density and free energy can be calculated by MD.

General neural-network-based force field Although deep learning methods have already shown their capabilities in accelerating AIMD, a neural network potential able to be generalized to different systems and simulation settings is of high practical value. This could be achieved by pre-training treatment and thus repeated work can be avoided, as users will no longer need to establish a model from scratch, but fine-tune the pre-trained models against specific systems instead. For example, a model describing arbitrary organic molecules at a very accurate quantum mechanics level will be useful in drug design, and a model describing any components of alloy/materials is valued in material science. Besides, the requirement of higher transferability also challenge current methods with more generalizable representation of atomic configuration, which further brings demand to architecture enhancement.

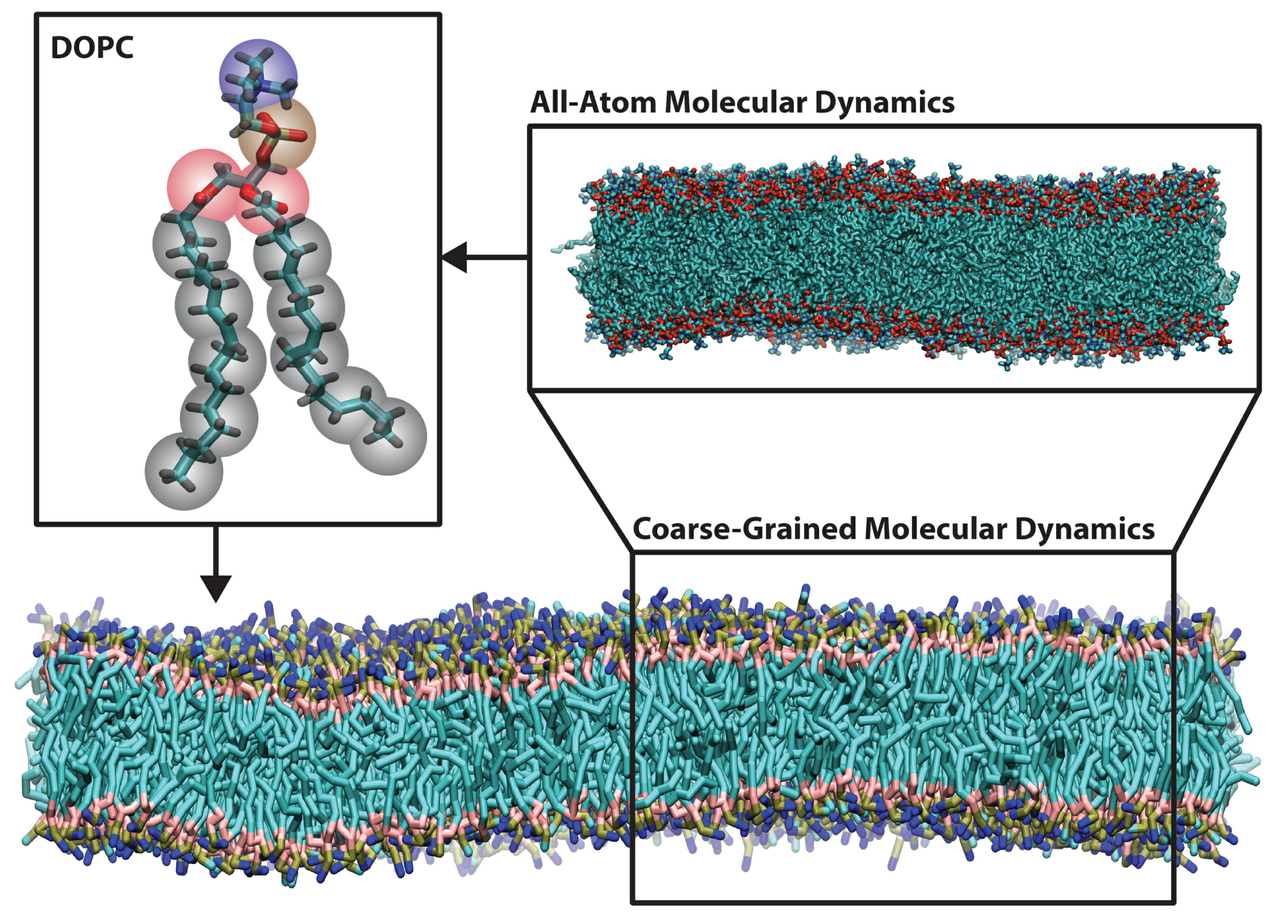

Coarse-grained models Simulation of extremely large and complicated systems, such as a whole virus, needs coarse-grained force fields that treat several atoms as one “bead”. Then the interactions between these beads are expected to reflect certain properties of interest, such as free energy or conformation distribution. However, it is nontrivial to find optimal forms and parameters to describe such interactions, and currently there are no general protocols like empirical atomistic force fields. AI models may be an effective tool just as they are between DFT/AIMD and classical MD, but more research need to be conducted to answer questions including what targets to fit, how to generate training data efficiently.

Enhanced sampling Enhanced sampling assists to overcome free energies barriers in a molecular dynamic simulation. If the free energy landscape of a given system is not smooth, the simulation will be stuck in one local minimal and ergodicity in molecular dynamics simulation will not be satisfied. This phenomenon is manifested by inadequate sampling over the whole landscape, especially over transition states or other local minima, and occurs frequently in simulation of biological systems. Computational chemists have employed bias-potential-based techniques (such as meta-dynamics [17], and umbrella sampling [18]) to enhance sample efficiency. But these methods require well-defined collective variables (CVs) and fail to handle situations where the number of CVs is large. The key challenge is how to learn an accurate representation of the free energy surface (FES) with high-dimensional CVs. AI models have recently been introduced, e.g., NN-VES [18], Reinforced Dynamics [19], and NN-based CV selections [20,21]. The main challenges lie in better models with generalizability and more effective workflows to take training data generation into consideration [22].

Partial differential equations

High dimensional partial differential equations (PDEs) arise in many scientific problems. Notable examples include high dimensional nonlinear Black-Scholes equations in finance, many electronic Schrödinger equations in quantum mechanics, and high dimensional Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equations in control theory. However, traditional numerical algorithms like finite difference or finite element methods suffer from the curse of dimensionality and are unable to deal with PDEs beyond 10 dimensions. The practical success of deep-learning-based PDE solvers such as physics-informed neural networks and deep BSDE method shows the ability of the deep neural networks to efficiently approximate the solutions of high dimensional PDEs. Hence, once we can reformulate the PDE by a variational problem, deep learning techniques can be easily applied to the variational problem and the original PDE can be solved. Successful examples in this direction include the deep Ritz method[23] the deep BSDE method[1] , and Physics-informed neural networks[24]

Variational problem: Find the maxima or minima of a functional, which maps functions to scalars, over a given domain.

Finite difference method: A class of numerical algorithms to solve the differential equations. It approximates the derivative or partial derivative by finite differences and solves the resulting linear or nonlinear systems.

Finite element method: A class of numerical algorithms to solve the differential equations. It converts the differential equations to a variational problem, uses a finite-dimensional linear space to approximate the domain of the variational problem, and solves the variational problem over the finite-dimensional linear space.

Control theory

Control algorithms are widely used in engineering and industry, which aim to govern the application of system inputs to drive the dynamic system to satisfying specific conditions. Since the time of Bellman [25] , a long-lasting problem in control theory is to solve the high dimensional closed-loop control problems, which aims to find the policy function: the input as a function of the state. Indeed, the terminology “curse of dimensionality” was originally coined by Bellman in order to highlight these difficulties. The practical success of deep learning shows that deep neural networks can approximate high dimensional functions and hence raise the hope to solve high dimensional closed-loop control problems. Although this field is still immature and faces many challenges such as stability and robustness of policy function, pioneering works [24,26] show the potential of this field. Another related field is reinforcement learning. Roughly speaking, control algorithms and reinforcement learning problems solve the same problems. However, in contrast, to control algorithms, which make heavy use of the underlying models, reinforcement learning algorithms make minimum use of the model. Comparison and combination of control algorithms and reinforcement learning algorithms are interesting topics and helpful if one wants to deal with complex practical problems.

Reinforcement learning: Reinforcement learning concerns how an agent takes actions to maximize the long-term reward when faced with an unknown environment. One feature of the reinforcement learning algorithm is that it does not require the exact form of the underlying model.

Fluid Mechanics

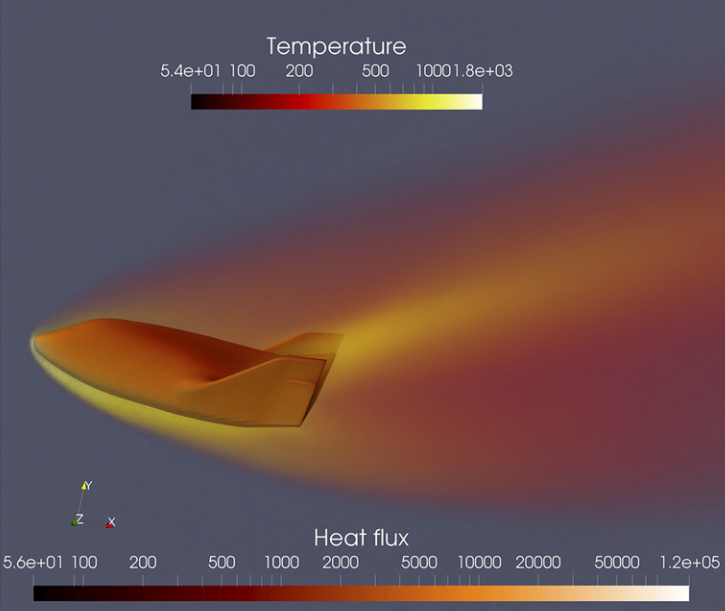

Fluid mechanics studies the systems with fluid (liquids, gases, and plasmas) at rest and in motion [27,28,29]. Many scientific and engineering disciplines get involved with fluid mechanics (as shown in Figure above), including astrophysics, oceanography, meteorology, aerospace engineering, chip industry, and physics-based animation. Overall, the fluid mechanics can be roughly divided into inviscid flows vs. viscous flows, laminar flows vs. turbulence, incompressible flows vs. compressible flows, continuum flows vs. rarefied flows, single-phase flows vs. multiphase flows, Newtonian flows vs. non-Newtonian flows, etc.

Mathematical analysis, experimental studies, and numerical simulations are three major approaches to exploring fluid mechanics. Fundamentally, a fluid system is assumed to be governed by mathematical equations in the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. In different physical modeling scales, the governing equations of fluid are in different forms [30], the newton dynamics, Boltzmann equation, Euler or Navier-Stokes equations (NSE), and coarse-grained turbulence models. In the hierarchy of governing equations, the hyperbolic Euler equations for inviscid flows are usually utilized to validate the performance of the numerical scheme of its accuracy, efficiency, and robustness. Additionally, the NSE is widely used in continuum viscous fluid mechanics, while the Boltzmann equation works well in rarefied gas dynamics. With the rapid growth of high-performance computing, numerical simulation called computational fluid dynamics (CFD) not only gradually becomes the indispensable tool to validate the key mathematical conclusions and experimental observations in fluid dynamics, but also provides more abundant and practical fluid information (macroscopic velocities, pressure and temperature distribution, drag and lift force, heat load, noise level) for engineering applications. With the aid of AI methods, research on numerical and experimental fluid mechanics may be improved.

Design data-driven turbulence models, such as modeling high-Reynolds number wall-bounded turbulent flows and complex separated turbulent flows [31] (i.e., the simulation and design in advanced aircraft).

Conduct data assimilation in flow fields, which combines the sparse measured data and numerical solutions together to provide more complete and accurate flow fields (i.e., the prediction of ocean circulation, weather forecast, and city environment simulations).

Refresh multiphase and multiscale fluid models, which modify the ad-hoc models of turbulence combustion, multiphase flows, and rarefied gas dynamics (i.e., efficient moment closure models for simulating rarefied flows).